Substitution model and environment model are two different mental models for understanding code

Functional programming

When we build an extensive system, the first problem we need to resolve is how we treat this system. The first opinion thinks the system will be combined with many objects; they will be changed as time goes by. And the second opinion thinks the data is just like the stream, and it flows through different processing stages. If you aren’t a time traveler from 1980, you will know these two opinions is Object-oriented programming & Functional programming actually, as we all understood.

The most significant advantage of functional programming is we don’t have state here. We can understand a program by using the substitution modal. Consider the following code:

(define (square x)

(* x x))

(define (sum-of-squares x y)

(+ (square x) (square y)))

(define (f a)

(sum-of-squares (+ a 1) (* a 2)))When we call the procedure (f 5), the interpreter of Lisp will return 136. We can consider this procedure step by step as if we were interpreters ourselves.

; invoke the procedure

(f 5)

; use the definition of procedure `f` to replace the `f`

(sum-of-squares (+ a 1) (* a 2))

; use the actual parameter to replace the formal parameter

(sum-of-squares (+ 5 1) (* 5 2))

; continue to replace the sum-of-squares procedure

(+ (square 6) (square 10))

; replace the square procedure finally

(+ (* 6 6) (* 10 10))

; and we will get the result

136What we do here means we can use substitution modal to understand our code; we don’t have any state in our function. Everything here is functional. If you have read some related posts before, you may understand it’s Functional programming.

In a functional system, procedures in each layer are pure, and they don’t have any state. We can understand them by using the substitution modal.

The best thing is, if we organize the program functionally, the system will be straightforward to understand. Why? Because we don’t have any state and environment, every procedure will return the same result in each invoke.

The magic of functional programming

You may think: well, using substitution modal to understand a piece of code sounds excellent, but it’s just a little while.

Before we see the real magic, let’s consider the data structure first. How do we build a new data structure? We can implement a constructor function and several select functions; they meet certain conditions. This definition is not strict enough but can explain the following things.

This definition can explain the high-level data, like rational numbers, and present some underlying data.

In Lisp, we have a kind of data structure called pair. We can use three procedures to control a pair: cons, car, cdr. And the specific condition these procedures should meet is: for random object x and y, if z equals (cons x y), so (car z) is x, and the (cdr y) is y. These procedures are basic in Lisp language, but we don’t need them. We don’t need any data structure, and we can only use the procedures. And here is the definition:

(define (cons x y)

(define (dispatch m)

(cond ((= m 0) x)

((= m 1) y)

(else (error "Argument not 0 or 1 -- CONS" m))))

dispatch)

(define (car z) (z 0))

(define (cdr z) (z 1))When we use cons, it will return a procedure, and when we invoke (car z), the procedure will be like this:

; we invoke the `car` procedure

(car z)

; use the substitution modal

(car (cons x y))

((cons x y) 0)

; the `cons` procedure will return the `dispatch`

(dispatch 0)

; here is the answer

xAs you can see, we erased the boundaries between data and procedure. We encapsulate the complex implementation at the underlying so that we can use this data elegantly and uniformly. The theory source of this magic is Church encoding. Church encoding is a means of representing data and operators in the lambda calculus, and the Church numerals are a representation of the natural numbers using lambda notation. You can read more information about it at Wikipedia.

Before we discuss how to use Lisp to implement it, we need to know the definition of natural numbers. According to the Peano axioms, natural numbers should meet these two rules:

- 0 is a natural number

- Each natural number should have the following natural number

Tip: This definition is not precise enough. You can read the Wikipedia to get more information about Peano axioms.

So, we can use Lisp to implement it:

(define zero

(lambda (f)

(lambda (x)

x)))

(define one

(lambda (f)

(lambda (x)

(f x))))

(define two

(lambda (f)

(lambda (x)

(f (f x)))))As you can see, each number is a procedure, they accept f as param, and the result will be a procedure that takes x as the param. The differentia is the number of times you apply f to x.

Furthermore, we can also implement the add procedure:

(define (add-1 n)

(lambda (f)

(lambda (x)

(f (n f) x))))

(define (add m n)

(lambda (f)

(lambda (x)

((m f) ((n f) x)))))You can use the substitution modal to understand this procedure. It’s a bit complex, but I’m sure that you can feel the magic of data encapsulation.

Assignment

But it’s not free; when you get some good things from the world, pay attention to some underlying bad things. When we implement a pure function in our system and enjoy the benefit, we may think, can we only use functional programming to organize every logic in our system?

Think about the following code. To say it, we want to implement a bank system:

(define (withdraw-generator balance)

(lambda (amount) (- balance amount)))It looks good, we use define to implement a procedure that will hold the balance for us, and this procedure will generate another procedure that we can use to remember the balance.

But when we invoke it, we will see something like this:

(define withdraw (withdraw-generator 100))

(withdraw 50)

; 50

(withdraw 20)

;80It looks wilder, we withdraw many times from the bank, but the money in the bank never changed! The reason for this, variables held by the inner function (it’s balance in our case) are locked by the outer environment. Every time we run this procedure, we will use the initial value.

You’ve probably already figured out the solution. Yep, it’s Assignment.

(define (withdraw-generator balance)

(lambda (amount)

(if (>= balance amount)

(begin (set! balance (- balance amount))

balance)

"Insufficient funds")))We can use this procedure like the following code:

(define withdraw (withdraw-generator 100))

(withdraw 20)

; 80

(withdraw 30)

; 50Every time we run this procedure, the balance value will be set as the new value. We resolved this problem! 🎉

Pandora’s box

When we haven’t introduced assignments to the programming world, everything is very pure. Data and procedure are the same, and we can use the substitution modal to understand the program.

But when we do that, it’s just like opening Pandora’s box. Everything will not be pure anymore, and the substitution model will also fail. We must introduce a new model to help us understand the program.

Before we discuss the cons of the assignment, we need to talk about environment.

As we all know, the value of a variable depends on what it points to. Consider the following code:

(define procedure (x)

x)This procedure will return the param x, and interpreters will determine x value during the runtime.

(define procedure (x)

y)But this code is different, the procedure accepts x as the param, but it returns y and the end of the procedure. What is the value of y? We don’t know. We need to check the environment of this procedure first, and then we will get the conclusion.

if the complete code is:

(define y 1)

(define procedure (x)

y)The result will be 1. Cause the interpreter can find that we define the variable out of the procedure and the value is 1.

In short, we don’t just need to care about the procedure itself, and we also need to care about the environment. This behavior breaks the encapsulation of the procedure and will lead to many potential dependency issues.

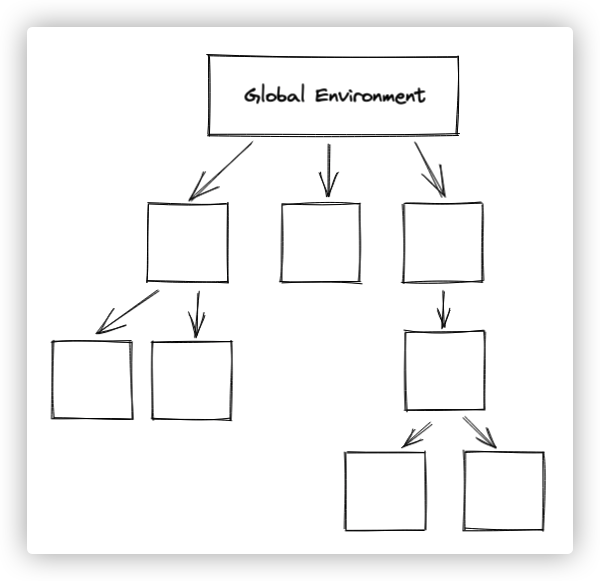

It should be mentioned that in actual code, the environment is a complex N-fork tree like the following graph.

We must always be careful not to place variables in a too high level of the environment tree. Otherwise, we will need to deal with complex implicit dependency problems.

Value passing and reference passing

To make the discussion clearer, let’s use C++ as the sample code.

I’m pretty sure we all understand the definition of value passing and reference passing. But let’s re-think it in the environment model.

void procedure1(int n) {

n++;

}

void procedure2(int &n) {

n++;

}Here we have procedure1 and procedure2. The former is value passing, and the latter is reference passing. If we consider these two procedures in the environment model, we will know a significant difference is:

The ability to change the upper environment

When the param of a procedure is value passing, we can only change the lower environment levels. On the contrary, if the param of a procedure is reference passing, we can change the lower and upper environments.

If we don’t understand our code well, unexpected assignments can mess up the code logic and make the system difficult to expand and maintain.