Overview

Heap sort is a comparison-based sorting technique based on the binary heap, but before jumping into the algorithm, it’s vital to talk about a data structure: Priority queue; it can help us to understand the binary heap and the mechanism of heap sort.

We will start with basic schedule theory and explain why priority queue is significant. After that, we will talk about its elementary implementation of it and a widespread implementation: binary heap representation. And of course, as two required methods of the heap, we will also talk about sink and swim.

As the last thing, we will talk about the heap-sort itself. At that moment, it will be straightforward to use the methods we discussed earlier to build the sorting algorithm.

The application of the priority queue is vital, but we can’t discuss too many details in this article. So we will briefly talk about popular systems that use priority queue as the primary data structure.

Queue

The queue is a vital data structure in computer programming. It’s a linear structure that stores information in a particular order, and the user of this data structure will process this information in that order. It looks like the stack, but for a normal queue, the order of data it stores is First In First Out (FIFO).

We can understand the queue from two aspects: processing order and underlying structure.

First is the processing order. The queue is like the stack; they define some rules to process data with some sequences. The sequence depends on the specific issues. The starting point for determining the order is the other theories like schedule theory.

A well-known example is the OS scheduler. To process multi-tasks, we need to design a scheduler that can generate a TODO list for CPU or other hardware. Different kinds of schedulers have various performances. A simple schedule strategy is the shortest job first (SJF). It’s easy to know if we use this scheduling strategy; our work is to implement a data structure that can return current work via the API.

Second is the underlying structure, it affects the way to implement the data structure. Two elementary way is using a linked list or array. We will talk about the detail later.

Priority queue

The priority queue is an abstract data structure just like a queue. It holds some data before it is processed. But as we mentioned, the key to the priority queue is the order of processing data. The priority queue doesn’t process data from the end of the queue; it always processes the data based on the priority level. In other words, the priority queue is a more generic abstraction of the queue. If we always give the lowest priority level of the new node and put it at the start of the priority queue, it will work like the standard queue.

There are two necessary methods to implement the priority queue: insert, which can add new data to the queue, and delMax, which can remove and return the current maximum data from the queue. We can use the interface to describe the functionality of the priority queue:

Note: there are two kinds of priority queues: the max priority and the min priority. The only difference is that del returns the current max or min priority level value. But we only discuss max priority queue here.

interface MaxPriorityQueue {

fun isEmpty(): Boolean

fun max(): Int

fun insert(v: Int)

fun delMax(): Int

}Implementation

In a nutshell, we some elementary ways to implement the priority, which is using the array or linked list. According to the rules of whether use the lazy approach, we can store the data ordered or unordered in the array. Taken as a whole, there is no difference between the two strategies. The only trade-off is when to place the computing task.

Another way is to use the Heap. Based on this excellent data structure, we can reduce the time complexity to .

| data structure | insert | remove max |

|---|---|---|

| ordered array | 1 | |

| unordered array | 1 | |

| heap |

Elementary implementation

The most straightforward way to implement a priority queue is using an array or linked list. According to the actual scenario, we can keep the data in priority queue order or unordered. The difference between these two strategies is the moment we used to find the current max/min priority level item.

Unordered array

If we decide to use an array to implement the priority queue, the most vital consideration is to handle the capacity of the underlying array. Go a step further; whenever the array expands or shrinks, we must walk through the entire array and process each item. This will become a performance bottleneck when there are many items in the array.

Because the array is unordered, when we want to remove and return the max priority level item, we need to iterate over the entire array, find that item, swap it with the last item of the array, and then remove it.

The code is pretty straightforward, and you can refer to this implementation.

Ordered array

Another approach is to put the item in the ordered position, thus, the largest item is always at the end. If we want to remove and return the largest item, we can pop the last item.

It’s easy to think that, on the one hand, this implementation still needs to deal with the array capacity; on the other hand, the difference with the unordered array is the main operational overhead that occurs when inserting new data in this approach.

For the insert method, we can use the bubbling policy. Put the data at the end first, and compare it with the previous one. If the value of it is larger than the previous one, swap them; otherwise, stop the code.

You can refer to this implementation.

Linked list

There is also a data structure that can represent a series of information, which is a linked list. Unlike an array, the capacity of a linked list is theoretically unlimited, which means we don’t need to do the expanding or shrinking work.

But the most significant disadvantage of a linked list is that we can’t find an item in a linked list in . Of course, many improved linked lists can decrease the time complexity, but we will skip them since they are not our major topic.

The insert and delMax methods are pretty straightforward. Just generate a new node using the data, and connect the new node to the front and back nodes.

By the way, a common trick to implementing a linked list is to add virtual nodes before and after the linked list, so that there is no need to make tedious judgments in the code.

You can refer to this implementation.

Binary Heap

As discussed earlier, we can also use the heap (binary heap) to implement priority queues.

In computer science, the heap data structure is a complete binary tree that satisfies the heap property, where any given node is:

- always greater than its child node/s, and the key of the root node is the largest among all other nodes. This property is also called max-heap property.

- always smaller than the child node/s, and the key of the root node is the smallest among all other nodes. This property is also called min-heap property.

Representation

A straightforward way to implement heap is using the node with three links. Two of them are linked to child nodes, and the third link is linked to the parent node. This design allows us to traverse the tree arbitrarily:

data class Node<V>(var value: V) {

var parent: Node<V>? = null

var leftChild: Node<V>? = null

var rightChild: Node<V>? = null

}But we notice that the heap is a complete binary tree, so we can use an array to store it actually. If we do that, the parent of the node in position is in position and, conversely, the two children of the node in position are in positions and .

Swimming and Sinking

For a priority queue, the most crucial functionality is insert and delMax.

The problem we need to consider is how to maintain the properties of the head after adding or deleting elements. Recall the logic of the insertion sorting algorithm. Every time we select an array element, we compare it with the previous one. If the current element is larger than the previous one, move the current element one step forward. Otherwise, stop here.

It’s easy to know that any path from the root node to a leaf node is a non-decreasing sequence for a heap. So suppose if I add a random comparable element at the end of the sequence, I broke the orderliness of the sequence. How can I fix it? Yep, use the logic of the insertion sorting algorithm. Comparing, moving, stop until everything is ordered.

According to the discussion above, we can design the insert and delMax methods.

For the insert, we will put it at the end of the priority queue. Please pay attention here; when we say the end of the priority queue, we mean the end of the underlying array since we use an array to represent the priority queue. It’s easy to know the new element is at the leaf position of the heap; in other words, it’s in a path or a sequence of the heap. For now, the method’s logic is pretty straightforward, just compare the new element with the previous one, move it if it’s larger than the previous one, and stop until it’s not. We call this procedure swim, and the following is the example code:

// this is the pointer to the current priority queue

fun swim(index: Int) {

while (index > 1 && this.queue[index / 2] < this.queue[index]) {

swap(this.queue, index / 2, index)

index /= 2

}

}Since we just need to compare the current node with the parent node in the swim method, so the comparison cost of it is .

For the delMax, it has almost the same logic as the insert. The only difference is that whenever we call the delMax for a max priority queue, we will delete and return the root node. And this logic is the same for the min priority queue. Let’s think about this logic. If we delete the root node directly, the tree will be broken into two sub-trees, and it’s difficult to merge two sub-trees and re-heap the result. So our strategy is to swap the root node and the last node and remove the element on the last position. After that, we can just compare the element on the root position with the two child node of it and move it on the path according to the comparison result. We call this procedure sink, and the following is the example code:

fun sink(index: Int) {

while (index * 2 <= this.size) {

val left = index * 2

val right = left + 1

// Swapping the current node with one of the children will make that child node the parent of the other node. So we need to find the larger one

if (left < this.size && this.queue[left] < this.queue[right])

left++

// stop sink

if (this.queue[index] > this.queue[left])

break

swap(this.queue, index, left)

index = left

}

}Since we need to compare the current node with two children nodes per level, the worst-case comparison cost will be .

Immutable key

One thing needs to be mentioned; in the previous chapters, we discussed putting the key in heap order. In a real application, the key is just a symbol that indicates the priority level of the data. So the real data structure of the element will be:

data class QueueElement<K: Comparable<K>, V>(var key: K, val value: V)Store the real information in the payload, and use the key to identify the priority of the information.

You must already notice that the key is our gist to sort. So no one wants the client side to change the key unexcepted. To achieve this, we can make the keys using an immutable class.

*Classes should be immutable unless there’s a very good reason to make them mutable. … If a class cannot be made immutable, you should still limit its mutability as much as possible. - Joshua Bloch

Heapsort

As we discussed, in a max-heap-implemented priority queue, we can pull elements from it in descending order. It looks like a sorting algorithm! We can implement a new sorting algorithm based on this idea:

fun <T: Compare<T>> sort(array: MutableList<T>) {

// 1. insert the elements from array into the heap

// 2. pull out the elements from the heap

}It’s easy to understand. And for each element insertion, the comparison cost should be ; we have elements from array, so the total comparison cost for this algorithm should be .

But the problem is this is not an in-place sorting algorithm, which means for elements, we need memory to store them. Thus, we do want to find an in-place version of this sorting algorithm, and the key is heapify the array, and keep removing the current max key until we get an ordered array.

Implementation

Based on the discussion above, we have transformed the problem into how to heapify a random array. The key is to know that the heap is a recursive data structure, which means if a tree is a heap, the left and right sub-trees are also heaps. In other words, if the left and right sub-trees are heaps, but the tree itself is not the heap, we can just invoke sink for the root node to make the entire tree to be a heap.

Notice that for each leaf node, since they don’t have any child node, so they also meet the requirements of the heap. That means we can process the original tree from the leaf nodes to the root node, call the sink for the current root node, and process level by level until we reach the root of the overall tree.

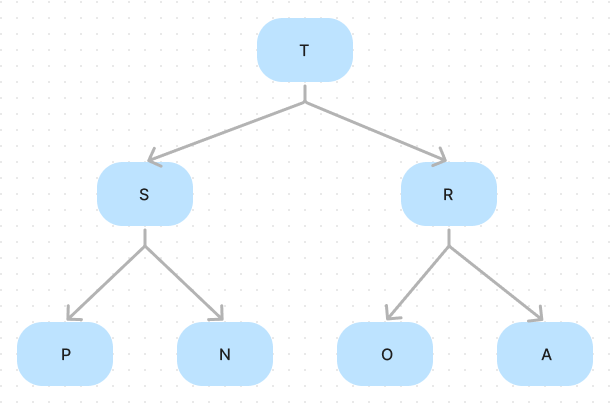

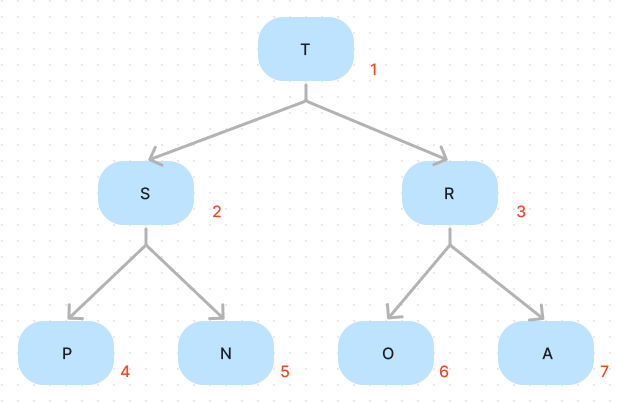

Consider the following tree:

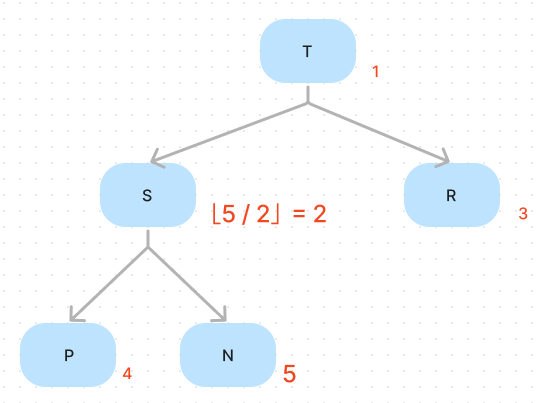

In this tree, we have three leaf nodes, R, P, N; they are heap right now, so we don’t need to process them. We can just start from the S. A more general term is, if we want to heapify a tree, we can start from the right-most inner node at the second level from the bottom. And it’s very easy to find; suppose the array has elements, and the inner node’s index will be . The following is the code:

// n is the array.length

for (k in n/2 downTo 1)

sink(k, n)After we get a heap, the next task will be to generate an ordered array. But we can’t just remove the top element and put it in another array since we want to implement an in-place sorting algorithm. This is super easy to implement, we can just follow the logic of the delMax method, exchange the root (max element) with the last element, and decrease the array’s length. Keep doing it until we get the result. So the code will be:

fun <T: Compare<T>> sort(array: MutableList<T>) {

var n = array.size

// Heapify the array

for (k in n/2 downTo 1)

sink(k, n)

// Generate the ordered array

while (n > 1) {

// exchange the root with the last element

swap(1, n--)

// Heapify

sink(1, n)

}

}Analysis

For the Generate the ordered array step. Removing the max element from the heap needs exchanges since we also need to re-heapify the array. And for elements, the exchange cost will be . A detail of this step is, that the comparison cost is twice as large as exchanging cost since for a node, it will be compared with two sub-nodes but only need exchange with one of them if necessary.

For the Heapify the array step. For a height tree, we need to process item. If we consider the worst case, for every level, every node sink to the bottom-most level.

So, for leaves, they don’t fall any levels since they already are heap. For , each node falls level and requires exchange total. Similarly, for , require . So we have:

We have:

Taking a derivative of both sides with respect to , we have:

And then multiplying by :

If we suppose , we have:

And we replace the with since it will be smaller, so we have inequalities:

Also, we have , so the exchange cost in the worst case is approximately . By the way, the comparison cost is .

Both of these are smaller than the first step’s complexity. As a result, the overall exchange and comparison costs for heapsort is .